📄 Introduction

Rust is happy to let you share your data… but only if you follow its strict borrowing etiquette. Break the rules, and the borrow checker will step in.

In our previous post on Ownership, we learned that every piece of data in Rust has exactly one owner — and once ownership moves, the old owner can’t use it anymore. But what if you just want to use someone else’s data without taking it away from them?

That’s where borrowing comes in. It’s like asking to borrow a friend’s pen: you can write with it, you might even carry it around for a while, but you must give it back exactly as you found it. Rust ensures this borrowing happens safely by preventing three common issues:

- Accidental overwrites — when multiple places try to modify the same data at once.

- Dangling references — when a reference points to memory that’s already gone.

- Memory leaks — when memory is never freed after use.

In the next sections, we’ll see what borrowing is, why it matters, and how to handle common borrowing errors with confidence.

📌 What is Borrowing?

Borrowing is Rust’s way of allowing temporary access to data without taking ownership of it. When you borrow a value, you use it through a reference, and when you’re done, the original owner still retains full control.

References are created using the & symbol for immutable borrows or &mut for mutable borrows:

let name = String::from("Rust");

let ref_to_name = &name; // borrowing 'name' immutably

Think of it like borrowing a friend’s pen — you can use it, but you must return it in the same condition. In programming terms, this means you can read or even modify the data (with rules), but you cannot take it away or destroy it.

Borrowing ensures:

- No two places can write to the same data at once.

- No place can read data that no longer exists.

With these safety rules in mind, let’s look at why we need borrowing and how it works in practice…

⁉️ Why We Use Borrowing in Rust?

Just like borrowing a friend’s pen saves you from buying a new one, borrowing in Rust lets you work with data without making unnecessary copies or giving up control of it.

Here’s why it’s important:

- Avoid unnecessary data copying – Borrowing lets you pass data to functions without making expensive clones (e.g., passing a large vector to a print function).

- Enable shared access – Multiple parts of your program can read the same data without conflict (e.g., two different modules displaying the same configuration).

- Control modifications – Mutable borrows allow changes, but in a controlled way that prevents race conditions (e.g., updating a score while no one else is reading it).

- Preserve the owner’s control – The original owner still decides when the value is dropped (e.g., memory for a string is freed when its owner goes out of scope).

Borrowing is one of Rust’s core safety tools, making it possible to work with complex data flows without losing track of who’s responsible for what. Now that we know why it’s important, let’s look into the two types of borrowing and see them in action.

🗂️ Types of Borrowing in Rust

⚠️ Immutable Borrow (&)

An immutable borrow is like looking at your friend’s notebook without making any marks — you can see everything but can’t change any thing. In Rust, you can have multiple immutable borrows to the same data at the same time.

Let’s understand immutable borrow with an example

fn main() {

let city = String::from("Tokyo");

print_length(&city); // pass immutable reference

println!("City is still accessible: {}", city);

}

fn print_length(name: &String) {

println!("Length is: {}", name.len());

}

Explanation:

| Line | Description |

|---|---|

let city = String::from("Tokyo"); |

Creates a String and assigns ownership to city. |

print_length(&city); |

Passes an immutable reference of city to print_length. The function can read the value but cannot change it. Ownership remains with city. |

fn print_length(name: &String) |

Declares a function with the parameter name, which is a reference to a String. |

println!("Length is: {}", name.len()); |

Prints the length of the string. After the function call, city is still fully accessible because ownership was not transferred. |

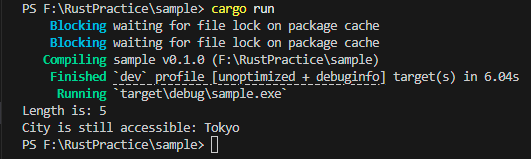

Screenshot : VS Code terminal output for immutable borrow example

💡 Try it yourself:

Replace "Tokyo" with any other city name and run the program — you’ll see the borrow works the same way.

But sometimes, you don’t just want to look at the data — you want to change it. That’s where mutable borrowing comes in.

📝 Mutable Borrow (&mut)

A mutable borrow is like asking your friend, “Can I use your notebook to add a few notes?” — you’re allowed to read and modify, but the rule is strict: only one mutable borrow can exist at a time, and it can’t coexist with immutable borrows.

Let’s understand mutable borrow with an example

fn main() {

let mut score = 50;

update_score(&mut score); // pass mutable reference

println!("Updated score: {}", score);

}

fn update_score(value: &mut i32) {

*value += 10;

}

Explanation:

| Line | Description |

|---|---|

let mut score = 50; |

Creates a mutable variable score with the value 50. |

update_score(&mut score); |

Passes a mutable reference of score to update_score. This allows the function to modify the original variable without taking ownership. |

fn update_score(value: &mut i32) |

Declares a function with the parameter value, which is a mutable reference to an i32. The expression *value dereferences it, and *value += 10; updates it by 10. |

| After the function call | score now holds 60 because the modification was applied directly through the mutable reference. |

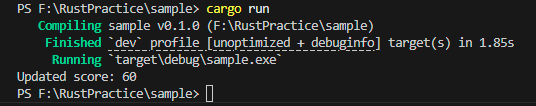

Screenshot : VS Code terminal output for mutable borrow example

💡 Try it yourself:

Change the increment from `10` to `25` and run it again — watch how the update applies directly to the original variable.

📦 Borrowing Rule Recap

To keep your borrows safe, Rust enforces these rules:

- Any number of immutable borrows (&T) at a time.

- Only one mutable borrow (&mut T) at a time.

- No mixing mutable and immutable borrows to the same data at the same time.

- A borrow must never outlive the data it refers to.

🔖 Ownership Vs Borrowing

| Feature | Ownership | Borrowing |

|---|---|---|

| Who controls the value? | The owner variable | The owner still controls it; borrower has temporary access |

| How long can you use it? | Until it goes out of scope | Until the borrow ends (function return, block end, etc.) |

| Does control move? | ✅ Yes | ❌ No – access is temporary |

| Can you modify it? | ✅ Yes, if it’s mutable | ✅ Yes, only with a mutable borrow (&mut) |

| Number of simultaneous accesses | One owner at a time | Many immutable borrows or one mutable borrow |

| When is memory freed? | When the owner goes out of scope | When the owner goes out of scope (borrowers don’t free memory) |

| Example | Moving a string into another variable | Passing a reference to a function without cloning |

🔍 Borrowing Errors & How to Fix Them

Rust’s borrow checker is like a strict librarian — it makes sure you return books on time, don’t scribble on someone else’s notes without permission, and never try to read a book that’s been thrown away. If you break the borrowing rules, Rust will stop compilation and show you an error.

Here are some common borrowing errors and how to fix them:

1️⃣ Mutable and Immutable Borrow Conflict

fn main() {

let mut name = String::from("Rustacean");

let r1 = &name; // immutable borrow

let r2 = &mut name; // mutable borrow in same scope

println!("{}, {}", r1, r2);

}

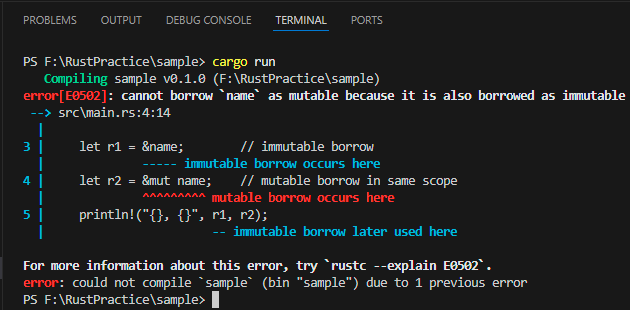

Error Message Screenshot:

Why it happens :

You can have multiple immutable borrows or one mutable borrow, but not both at the same time.

How to fix:

Use immutable borrows first, then create the mutable borrow after they’re done being used.

fn main() {

let mut name = String::from("Rustacean");

{

let r1 = &name;

println!("{}", r1); // immutable borrow ends here

}

let r2 = &mut name;

println!("{}", r2);

}

💡 Try it yourself:

- Run the first code snippet to see the borrow checker error in your terminal.

- Then run the fixed version and verify that it compiles and prints the expected output.

- Challenge : Can you restructure the code so both borrows are valid without changing the printed values?

2️⃣ Borrow Outliving Its Data (Dangling Reference)

fn main() {

let r;

{

let s = String::from("Rust");

r = &s; // `s` will be dropped at the end of this block

}

println!("{}", r); // ERROR

}

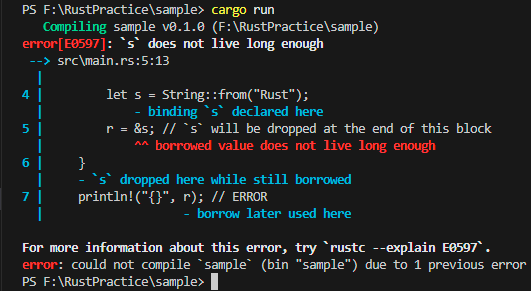

Error Message Screenshot:

Why it happens:

r points to data (s) that no longer exists once the inner block ends.

How to fix:

Return the owned value instead of a reference.

fn main() {

let s = String::from("Rust");

let r = &s;

println!("{}", r);

}

💡 Try it yourself:

- Run the error version to see the lifetime error in the terminal.

- Then run the fixed version and check that it works.

- Challenge : Write your own dangling reference example and fix it.

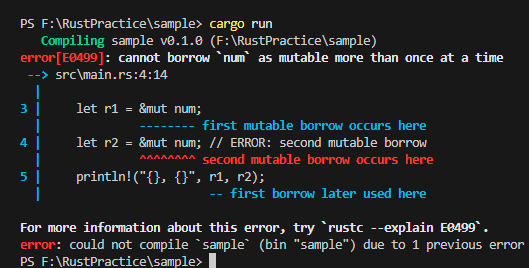

3️⃣ Multiple Mutable Borrows

fn main() {

let mut num = 10;

let r1 = &mut num;

let r2 = &mut num; // ERROR: second mutable borrow

println!("{}, {}", r1, r2);

}

Error Message Screenshot:

Why it happens:

Only one mutable borrow is allowed in a given scope to prevent data races.

How to fix:

We can solve this by making sure each mutable borrow is used and dropped before creating another one.

fn main() {

let mut num = 10;

{

let r1 = &mut num;

*r1 += 5;

}

let r2 = &mut num;

*r2 += 10;

println!("{}", num);

}

💡 Try it yourself:

- Run the error version to see the “already borrowed” message in your terminal.

- Then run the fixed version and confirm it compiles and updates the value as expected.

- Challenge : Modify the code so both updates happen in separate functions while still following borrow rules.

📝 Try it Yourself! - Example

Here is a simple example that helps you to understand borrowing in rust

fn main() {

let mut student_name = String::from("Manjusha");

// Immutable borrow - viewing student name

display_name(&student_name);

// Mutable borrow - updating student name

update_name(&mut student_name);

println!("Final student record: {student_name}");

}

fn display_name(name: &String) {

println!("Viewing student record: {name}");

}

fn update_name(name: &mut String) {

name.push_str(" (Class Representative)");

println!("Student record updated!");

}

💡 Try it yourself:

- Change the display_name(&student_name) call to display_name(&mut student_name). Will this throw an error or still display the output?

- Move the display_name call after update_name and check if it still works.

🎯 Conclusion

Borrowing is Rust’s way of letting you use data without taking ownership, ensuring safe and efficient memory management. Whether you borrow immutably or mutably, the rules are simple but powerful — follow them, and you avoid many pitfalls common in other languages.

Borrowing and ownership together form the backbone of Rust’s memory safety guarantees. But there’s one more piece of the puzzle: lifetimes — they decide how long your borrows can live and ensure they’re always valid.

🔄 What’s Next on Techn0tz?

In the next post, we’ll explore:

Cracking Rust Lifetimes – Learn Borrowing & Explicit Rules the Easy Way