📄 Introduction

Data structures are simply ways to store and organize data so our programs can work faster and cleaner. Instead of juggling random variables everywhere, we group related values into arrays, lists, maps, trees, or queues so they’re easier to manage, search, and update. Whether it’s storing students in a class, tracking attendance, or quickly finding a record by roll number, the right data structure turns messy logic into predictable and efficient code.

Rust approaches data structures a little differently compared to many other languages. Rather than giving you everything as loose, dynamic containers, Rust focuses on safety, ownership, and performance. You get powerful built-in collections like Vec, HashMap, VecDeque, and BTreeMap that are fast, memory-safe, and production-ready, which means the same structures you practice with are the ones you’ll actually use in real applications. In this post, we’ll keep things practical and learn each structure using small runnable programs instead of theory. Let’s dive in

All examples below can be copied into

main.rs. Open a terminal inside your project folder and runcargo run.

Core Data Structures in Rust (With Runnable Examples)

Now let’s look at the data structures you’ll actually use while building real Rust applications. No heavy theory — just small runnable programs so you can copy, run, and see the behavior instantly.

Vec (Dynamic Array)

A Vec (vector) is a growable array stored on the heap. It’s the most commonly used collection in Rust because you can dynamically add, remove, and iterate over items with ease. If you ever need to store a list of values whose size can change, Vec is usually your first choice.

fn main() {

let mut students = Vec::new();

//names are for illustration only//

students.push("Riya");

students.push("Anita");

students.push("Manu");

println!("Total students: {}", students.len());

for s in &students {

println!("{s}");

}

}

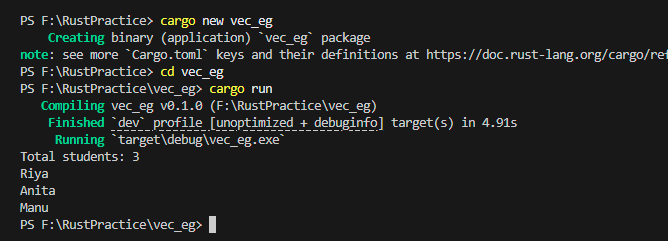

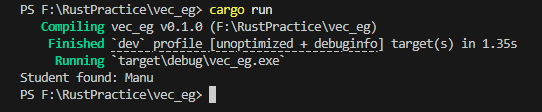

Screenshot: Students stored and printed in the same order they were added.

Real-World Usage:

- In real projects, Vec is everywhere — it’s probably the collection you’ll use daily.

- In my Teacher Assistant app, we use it to:

- store student lists

- keep attendance records

- hold marks or grades

- display ordered data in the UI

Add one more student name and print only students whose name starts with A

⏳ Try writing this on your own before checking the solution!

✅ Show Solution

fn main() {

let mut students = Vec::new();

//names are for illustration only//

students.push("Riya");

students.push("Anita");

students.push("Manu");

students.push("Rena");

for s in &students {

if s.starts_with('R'){

println!("{s}");

}

}

}Arrays (Fixed Size)

Rust also provides fixed-size arrays written like [T; N]. Unlike Vec, arrays live on the stack and their size must be known at compile time. You can’t grow or shrink them, which makes them less flexible for most real-world applications.

They’re useful for small, constant-sized data or simple buffers, but in day-to-day Rust development you’ll almost always prefer Vec because it can grow dynamically.

fn main() {

let marks = [85, 90, 78, 92, 88];

// indexing starts at 0

println!("First element: {}", marks[0]);

}

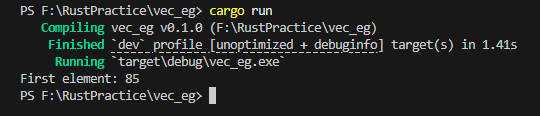

Screenshot: Accessing elements by index from a fixed-size array.

Since arrays are fixed and limited, most higher-level data structures in Rust are actually built on top of Vec.

And interestingly, we can even use a Vec itself to build other structures — like a stack.

Stack (using Vec)

A stack follows the Last In, First Out (LIFO) rule — the last item you add is the first one you remove.

Think of it like stacking books: you always take the top one first.

Rust doesn’t have a separate Stack collection because we don’t really need one. A Vec already provides everything required to behave like a stack using push() and pop().

fn main() {

let mut stack = Vec::new();

stack.push("Math");

stack.push("Science");

stack.push("English");

//pop() returns Option<T> → Some(value) or None if empty

let removed = stack.pop();

println!("Raw pop result: {:?}", removed);

if let Some(subject) = removed {

println!("Removed subject: {}", subject);

}

println!("Current stack: {:?}", stack);

}

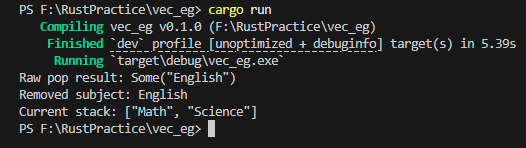

Screenshot: Last inserted element removed first — demonstrating LIFO behavior.

Real-World Usage:

Stacks are useful when you need to process the most recent action first:

- undo/redo operations

- browser back navigation

- expression evaluation

- temporary history tracking

Even in apps like a Teacher Assistant system, a stack can help manage recent changes or temporary actions that may need to be reverted.

Push 5 values, pop them twice and print the final stack. What will be the output?

⏳ Try writing this on your own before checking the solution!

✅ Show Solution

fn main() {

let mut stack = Vec::new();

// push 5 values using a loop

for i in 1..=5 {

stack.push(i * 10);

}

// pop twice

stack.pop();

stack.pop();

println!("{:?}", stack);

}Queue (using VecDeque)

A queue follows the First In, First Out (FIFO) rule — the first item you add is the first one removed.

Think of it like a line at a ticket counter: the person who comes first gets served first.

While a Vec is great for stacks, removing elements from the front of a Vec is slow because everything has to shift. Rust solves this with VecDeque (double-ended queue), which allows fast insertion and removal from both ends.

use std::collections::VecDeque;

fn main() {

let mut queue = VecDeque::new();

queue.push_back("Riya");

queue.push_back("Anita");

queue.push_back("Manu");

let removed = queue.pop_front();

println!("Raw pop result: {:?}", removed);

if let Some(name) = removed{

println!("Removed name: {}", name);

}

println!("Remaining queue: {:?}", queue);

}

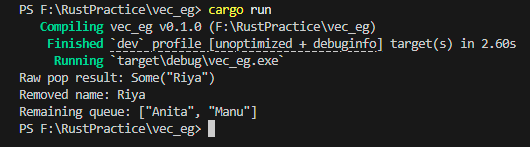

Screenshot: First inserted element removed first — demonstrating FIFO behavior.

Real-World Usage:

Queues are useful when you need to process tasks in the same order they arrive:

- task scheduling

- request handling

- message processing

- attendance processing

In practical app like Teacher Assistant, a queue is helpful to process students one-by-one for attendance marking or generating reports sequentially.

• Add 4 numbers using push_back()

• Remove one using pop_front()

• Add one more

• Print the final queue

What order do you expect?

⏳ Try writing this on your own before checking the solution!

✅ Show Solution

use std::collections::VecDeque;

fn main() {

let mut queue = VecDeque::new();

// push 4 values using a loop

for i in 1..=4 {

queue.push_back(i * 10);

}

// pop the first value

queue.pop_front();

//push one more value

queue.push_back(50);

println!("{:?}", queue);

}HashMap (instant look up with Keys)

Imagine you have 500 students and you want to find one student using their roll number.

If everything is stored in a Vec, you’d have to scan the list one by one — slow and inefficient.

This is exactly where a HashMap shines.

A HashMap stores data as key → value pairs, so instead of searching through everything, you jump directly to the record using a unique key.

Think of it like:

- roll number → student name

- student ID → full record

- subject → marks

This gives you almost instant lookups (O(1)), which makes HashMap one of the most useful collections in real-world Rust applications.

use std::collections::HashMap;

fn main() {

let mut students = HashMap::new();

students.insert("10A01", "Riya");

students.insert("10A02", "Anita");

students.insert("10A03", "Manu");

let roll = "10A03";

match students.get(roll) {

Some(name) => println!("Student found: {}", name),

None => println!("Not found"),

}

}

Screenshot: Direct lookup using a key returns the value instantly (no scanning).

Real-World Usage:

HashMap is extremely common in backend and app development:

- fast lookups by ID

- caching data

- counting frequency

- configuration storage

Inside the TA app, this datastruture is perfect for:

- roll number → student details

- student ID → marks

- quick search without scanning the entire list

Instead of checking every student one by one (slow), we directly jump to the record instantly.

• Insert 4 subjects with their marks

• Fetch one subject using .get()

• Print the result

• Example idea: "Math" → 95

"Science" → 88

Can u retrieve just the English mark?

⏳ Try writing this on your own before checking the solution!

✅ Show Solution

use std::collections::HashMap;

fn main() {

let mut marks = HashMap::new();

marks.insert("Math", 95);

marks.insert("Science", 88);

marks.insert("English", 90);

marks.insert("History", 85);

let mark = marks.get("English");

println!("Raw result from Hashmap: {:?}", mark);

if let Some(number) = mark{

println!("The Actual mark: {}", number)

}

}BTreeMap (Sorted Key–Value Store)

A BTreeMap is very similar to a HashMap — it also stores data as key → value pairs.

But there’s one big difference:

👉 keys are always kept sorted.

While HashMap focuses on the fastest possible lookup, BTreeMap focuses on ordered data.

So when you iterate over it, items automatically come out in sorted order.

Think of it like:

- marks sorted by roll number

- students sorted alphabetically

- reports sorted by rank

Whenever order matters, BTreeMap is usually a better choice than HashMap.

With BTreeMap, whatever you choose as the key decides the sorting order.

⚠️ Note: If your keys are strings, sorting is lexicographical (dictionary order), not numeric.

For example,

"2"comes before"10". Use numeric types likei32if you need true numeric ordering.

use std::collections::BTreeMap;

fn main() {

let mut ranks = BTreeMap::new();

//BTreeMap<Key, Value>

ranks.insert(3, "Anita");

ranks.insert(1, "Riya");

ranks.insert(2, "Manu");

for (rank, name) in &ranks {

println!("Rank {} -> {}", rank, name);

}

}

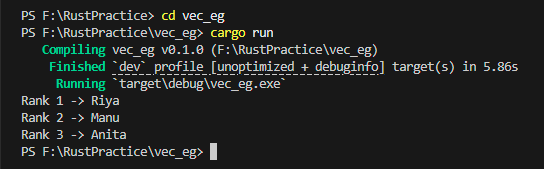

Screenshot: Items automatically printed in sorted key order.

Real-World Usage:

BTreeMap is useful when sorted results are important:

- leaderboards or ranks

- sorted reports

- range queries

- ordered logs

In the Teacher Assistant app, this is helpful for:

- displaying students sorted by roll number

- generating rank lists

- showing marks in order

- producing clean reports

With HashMap, sorting is manual. With BTreeMap, it’s automatic.

• Insert 5 subjects with their marks

• Print them using a loop

• Check if the output is sorted by subject name

What order do you expect?

⏳ Try writing this on your own before checking the solution!

✅ Show Solution

use std::collections::BTreeMap;

fn main() {

let mut marks = BTreeMap::new();

marks.insert("Science", 95);

marks.insert("Maths", 100);

marks.insert("English", 90);

marks.insert("Social", 80);

marks.insert("Language", 88);

for (subject, mark) in &marks {

println!("{} -> {}", subject, mark);

}

}Searching Techniques

Linear Search (Scan One by One)

Linear search is the simplest searching technique.

You start from the beginning and check each element one by one until you find the match.

It’s easy to implement, but not very fast for large data because in the worst case you may have to scan the entire list.

If you’re using a Vec and don’t have any special structure like HashMap or sorted data, this is usually what happens behind the scenes.

fn main() {

let students = vec!["Riya", "Manu", "Rose", "Anita"];

let target = "Rose";

let mut found_index = None;

for (i, name) in students.iter().enumerate() {

if *name == target {

found_index = Some(i);

break;

}

}

match found_index {

Some(i) => println!("Found at index {}", i),

None => println!("Not found"),

}

}

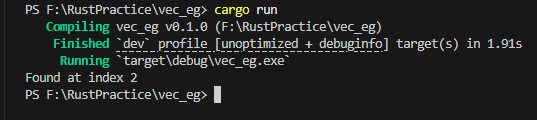

Screenshot: Element found after scanning sequentially through the list.

Real-World Usage:

Linear search is fine when:

- the list is small

- performance isn’t critical

- you only search occasionally

But for large datasets, it becomes slow because the time complexity is O(n).

For example, in the TA app:

- scanning 10 students → fine

- scanning 10,000 students repeatedly → slow

That’s exactly why we used a HashMap earlier — it lets us jump directly to a record instead of scanning every time.

• Search for Riya

• Print whether she exists

• If not found, println!("Student missing");

Can you modify the loop?

⏳ Try writing this on your own before checking the solution!

✅ Show Solution

fn main() {

let students = vec!["Riya", "Manu", "Rose", "Anita"];

let target = "Riya";

let mut found = false;

for name in &students {

if *name == target {

found = true;

break;

}

}

if found {

println!("Student exists");

} else {

println!("Student missing");

}

}Binary Search (Fast Search on Sorted Data)

Binary search is a faster searching technique that works only on sorted data.

Instead of checking elements one by one like linear search, it repeatedly divides the list into half.

Think of it like guessing a number:

- go to the middle

- if the value is smaller → go left

- if bigger → go right

Each step cuts the search space in half, which makes it much faster.

That’s why binary search runs in O(log n) time.

fn main() {

let mut nums = vec![78, 85, 90, 92, 95, 60];

nums.sort(); // required

println!("Sorted: {:?}", nums);

match nums.binary_search(&90) {

Ok(i) => println!("Found at index {}", i),

Err(_) => println!("Not found"),

}

}

⚠️ Note: Binary search picks the middle using

mid = (low + high) / 2For even-sized lists, Rust simply chooses the lower middle index.

The split doesn’t need to be perfect — just roughly half.

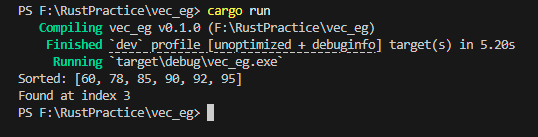

Screenshot: Element found quickly after sorting and halving the search space.

Real-World Usage:

Binary search is useful when:

- data is already sorted

- frequent searching is required

- performance matters

For example, in the Teacher Assistant app binary search is perfect for:

- sorted marks list

- sorted roll numbers

- rank lists

Instead of scanning every student, we can jump directly to the middle and narrow it down quickly.

But remember: binary search only works on sorted data.

If the list isn’t sorted, you must sort it first.

• Create a vector with numbers [40, 10, 70, 20, 90, 50]

• Sort it

• Print the sorted numbers

• Search for 40 using binary_search()

• Print the index

⏳ Try writing this on your own before checking the solution!

✅ Show Solution

fn main() {

let mut nums = vec![40, 10, 70, 20, 90, 50];

nums.sort();

println!("Sorted: {:?}", nums);

match nums.binary_search(&40) {

Ok(index) => println!("Found at index {}", index),

Err(_) => println!("Not found"),

}

}Sorting Techniques (Built-in and Practical in Rust)

Sorting simply means arranging data in a specific order — ascending, descending, or based on a custom rule.

Instead of implementing algorithms like bubble sort or quick sort manually, Rust already provides fast and optimized built-in methods. In real applications, we almost always use these built-ins directly.

The most common ones are:

sort()→ default ascendingsort_by()→ custom comparisonsort_by_key()→ sort using a field/key

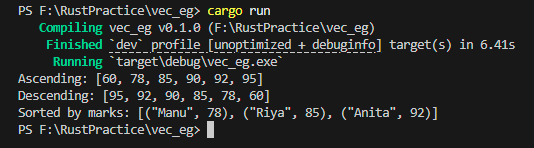

fn main() {

// sort()

let mut nums = vec![78, 85, 90, 92, 95, 60];

nums.sort();

println!("Ascending: {:?}", nums);

// sort_by() → descending

nums.sort_by(|a, b| b.cmp(a));

println!("Descending: {:?}", nums);

// sort_by_key()

let mut students = vec![

("Riya", 85),

("Anita", 92),

("Manu", 78),

];

students.sort_by_key(|student| student.1);

println!("Sorted by marks: {:?}", students);

}

Screenshot: Ascending sort, descending sort, and key-based sorting demonstrated.

Real-World Usage: Sorting is extremely common in real apps:

- marks in ascending/descending order

- rank lists

- alphabetical student names

- generating clean reports

In practical apps like Teacher Assistant, we often sort:

- marks before ranking

- students before display

- reports before exporting

Once sorted, we can also use binary search efficiently.

Create a list of students with (name, marks) and:

• sort by marks (ascending)

• then sort by name (alphabetical)

• print both results

Can you do it using sort_by_key() only?

⏳ Try writing this on your own before checking the solution!

✅ Show Solution

fn main() {

let mut students = vec![

("Riya", 88),

("Manu", 95),

("Rose", 78),

("Anita", 90),

];

// sort by marks

students.sort_by_key(|s| s.1);

println!("By marks: {:?}", students);

// sort by name

students.sort_by_key(|s| s.0);

println!("By name: {:?}", students);

}Big-O Complexity (Quick Practical View)

You’ll often hear terms like O(1), O(n), or O(log n) when talking about data structures.

Don’t worry about the math — think of Big-O as a quick way to compare how fast an operation grows as data increases.

Instead of memorizing formulas, just remember which structure is faster for which task.

| Operation | Structure | Complexity | What it means |

|---|---|---|---|

| Add item | Vec::push() |

O(1) | very fast |

| Search item | Linear search | O(n) | checks one by one |

| Search item | Binary search | O(log n) | halves each step |

| Lookup by key | HashMap |

O(1) | almost instant |

| Sorted lookup | BTreeMap |

O(log n) | fast + ordered |

| Sorting | sort() |

O(n log n) | efficient general sort |

👉 Quick tip: Use

Vecfor lists,HashMapfor fast lookup,BTreeMapfor sorted data.

Other Useful Collections in Rust (Quick Overview)

Rust also provides a few more specialized collections.

You may not use them daily, but it’s good to know they exist.

| Collection | When to Use | Notes |

|---|---|---|

LinkedList |

frequent insert/remove in middle | rarely used, Vec is usually faster |

BinaryHeap |

priority queue | always gives highest/lowest element first |

HashSet |

unique values only | like HashMap without values |

BTreeSet |

sorted unique values | ordered version of HashSet |

| Graphs | networks/path problems | usually built manually or using crates |

For most applications, Vec, HashMap, VecDeque, and BTreeMap are more than enough.

Rust vs Other Languages – Quick Mapping

If you’re coming from Python, Java, or C++, here’s a quick mental mapping:

| Concept | Rust | Python | Java | C++ |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dynamic array | Vec |

list | ArrayList | vector |

| Fixed array | [T; N] |

tuple/list | array | array |

| Stack | Vec |

list | Stack/Deque | stack |

| Queue | VecDeque |

deque | Queue/Deque | deque |

| Hash map | HashMap |

dict | HashMap | unordered_map |

| Sorted map | BTreeMap |

— | TreeMap | map |

| Set | HashSet |

set | HashSet | unordered_set |

So if you know these structures in other languages, you already know most of Rust’s collections too — just different names.

Conclusion

Data structures aren’t about memorizing theory — they’re about choosing the right tool for the job. Rust already gives you fast, safe, and practical collections out of the box, so most of the time you can focus on building features instead of implementing algorithms from scratch.

Try running the examples, tweak the code, and experiment a little.

Quick Recap

If you remember just these, you’re good to go:

- Vec → simple lists

- HashMap → fastest lookups

- VecDeque → queues (FIFO)

- BTreeMap → sorted data

- sort() → built-in sorting

That’s enough to build most real-world Rust apps.

Once you start using these structures in real projects, they’ll feel natural — and that’s when everything really clicks.

I’ll be sharing more Rust concepts and the Teacher Assistant Level 3 progress soon — see you on Techn0tz 🙂