📄 Introduction

“Ownership and borrowing keep Rust safe, but lifetimes ensure your references never outlive the data they point to.”

“Imagine lifetimes as invisible timers, starting the moment you borrow and stopping exactly when the data vanishes.”

In our earlier posts, we explored Ownership and Borrowing — the twin pillars of Rust’s memory safety. They handle most cases, but sometimes the compiler still throws the dreaded error:

“borrowed value does not live long enough…”

This is where lifetimes step in. They act as contracts between your code and the compiler, describing how long references remain valid and ensuring you never touch memory after it’s gone.

“Think of lifetimes like the expiry dates on borrowed items — you’re free to use them, but only while they’re valid. Once the date passes, the memory is no longer safe to touch.”

Here’s why lifetimes matter in Rust:

- Zero runtime cost → Lifetimes exist only at compile time, so safety comes for free.

- No dangling references → Prevents you from using memory that’s already gone.

- Tracks dependencies → Lets the compiler know how inputs and outputs depend on each other.

- Mostly automatic → Rust infers lifetimes for you, but you can step in with explicit annotations when needed.

In the next section, we’ll dive into what lifetimes mean in Rust, and how this concept silently powers memory safety.

📑 What are Lifetimes

A lifetime is simply the scope during which a reference is valid.

- Every reference carries an invisible clock — ticking from the moment you borrow until the owner goes out of scope.

- Most of the time, the compiler figures these clocks out for you.

- Sometimes you’ll need to write them explicitly using annotations like

'a.

Unlike variables or values, lifetimes don’t exist at runtime. They’re compile-time markers that help the compiler track how long references remain safe to use.

⁉️ Why are Lifetimes important?

Lifetimes are the reason Rust can prove that your references are always valid. Instead of letting memory errors sneak in at runtime (like in many other languages), Rust enforces these rules during compilation.

This prevents dangerous mistakes such as:

- Returning references to values that no longer exist → like giving back a library book after its due date, then trying to lend it again.

- Using a borrowed value after its owner has been dropped → like keeping a key after the house has already been sold.

- Mixing references that live for different durations → like trying to use a day-pass ticket to enter a year-long event.

For example, this function looks harmless but fails to compile:

fn main() {

let a;

{

let b = 10;

a = &b; // ❌ `b` does not live long enough

}

println!("a : {a}");

}

Explanation:

| Line | Description |

|---|---|

let a; |

Declares a variable a, but uninitialized. |

{ let b = 10; ... } |

New block → b exists only within this block’s scope. |

a = &b; |

Tries to store a reference to b inside a(i.e) a is borrowing b. |

} |

The inner block ends → b is dropped (goes out of scope). The reference stored in a now points to invalid memory. |

println!("a : {a}"); |

Rust stops compiling, because using a here would mean accessing a reference to already-freed memory. |

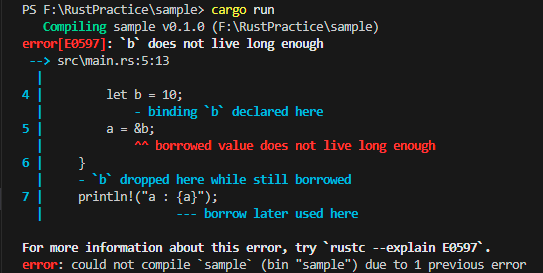

Error Message Screenshot: The compiler throws a “borrowed value does not live long enough” error before the program can run.

In simple terms, It’s like borrowing a book from a friend who immediately moves away and takes the book back. You still think you’re holding the book (the reference), but in reality, it’s gone. Rust refuses to let that situation even compile.

💡 Try it yourself:

👉 Can you fix the program so the reference stays valid?

- Move the `println!` inside the block

- Or make b live long enough to match `a`.

Which version compiles, and why?

This is why lifetimes are often called the third guardrail in Rust’s memory safety model — working hand-in-hand with ownership and borrowing to keep your references safe.

Next, let’s uncover the different kinds of lifetimes Rust uses — and see how you can annotate them explicitly.

🗃️ Types of Lifetimes

In Rust, lifetimes come in three flavors:

- Explicit lifetimes → when you must annotate how long references live.

- Static lifetime → the longest possible lifetime, lasting for the whole program (In the next part).

- Lifetime elision → shorthand rules where Rust figures things out for you (In the next part).

Let’s begin with explicit lifetimes, since they’re the most hands-on.

📝⏳ Explicit lifetimes

By default, Rust applies lifetime elision rules to figure out how long references live. But sometimes the compiler can’t deduce it — and that’s where explicit lifetimes come in.

An explicit lifetime is a user-defined label (like 'a, 'b) you attach to references. It doesn’t change the data — it just clarifies how long those references remain valid relative to each other.

“Think of it like the expiry date on packed food—the label doesn’t change the food itself but clearly tells you how long it’s safe to consume. Similarly, lifetimes don’t change your data but specify how long references remain valid.”

Explicit lifetimes can be broadly categorized into two types: single lifetime (when all references share the same lifetime) and multiple lifetimes (when different references have distinct lifetimes).

1️⃣ Single lifetime

A single lifetime means that all references in a function (or struct) are tied to the same scope of validity, represented by a single lifetime parameter (like 'a).

In simple terms, the compiler guarantees that any returned or borrowed reference will remain valid for the entire duration of 'a.

You typically use a single lifetime when your function works with one borrowed source of data, or when multiple references need to share the same validity period.

Imagine, 🚆 Single Lifetime as a Local Train Ticket,

- A local train ticket says: “Journey must commence within 1 hour.”

- Everyone with a ticket must finish their journey within the same time window.

- Once it expires, no one can use it — whether they reached their destination or not.

🔗 Likewise, in Rust:

- All references tied to

'ashare the same scope of validity. - Once

'aends, none of those references remain valid.

Let’s understand single lifetime with the example below:

fn longest<'a>(x: &'a str, y: &'a str) -> &'a str {

if x.len() > y.len() {

println!("The length of x is: {}", x.len());

x

} else {

println!("The length of y is: {}", y.len());

y

}

}

fn main() {

let string1 = String::from("Rust");

let string2 = String::from("Programming");

let result = longest(&string1, &string2);

println!("The longest string is: {}", result);

}

Explanation:

| Code | Explanation |

|---|---|

fn longest<'a>(x: &'a str, y: &'a str) -> &'a str { |

Defines longest with one lifetime 'a. Both inputs and the output share this lifetime, ensuring the returned reference is valid as long as both inputs are. |

if x.len() > y.len() {...} |

Compares the lengths and returns one reference. The 'a lifetime ensures whichever branch is chosen, the reference remains valid. |

let string1 = String::from("Rust"); |

Allocate a heap-stored string string1. |

let string2 = String::from("Programming"); |

Allocate a heap-stored string string2. |

let result = longest(&string1, &string2); |

Pass two references into longest. Rust checks that both live at least as long as 'a, making the return safe. |

println!("The longest string is: {}", result); |

Safe to use result here, because Rust enforced lifetime rules and guaranteed it doesn’t outlive its borrowed data. |

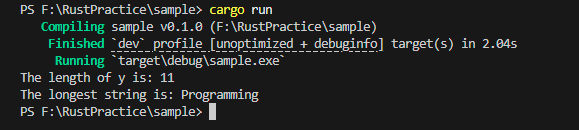

Screenshot: VS code terminal for finding longest string

So far, we’ve seen lifetimes with strings — but what if we want to use a single lifetime with something simpler, like integers?

Here’s a side-by-side comparison: when you return an owned value vs when you work with references.

| Owned Value (takes ownership) | Reference (borrows value) |

|---|---|

fn cal_square(num: i32) -> i32 { |

fn cal_square(num: &i32) -> i32 { |

Output: x = 4 |

Output:x = 4 |

Note:

In both cases, we don’t use lifetimes ('a, 'b) because the function does not return a reference. It only takes in data, does the calculation, and returns a new owned value (i32). Lifetimes are only needed when references are returned or when multiple references must be related in scope.

👉 But what if your function needs to handle two references that don’t share the same validity? That’s when we step into multiple lifetimes…

2️⃣ Multiple Lifetimes

Earlier, with a single lifetime, the function works with just one reference parameter ('a). In contrast, with multiple lifetimes, the function can accept more than one reference, and the compiler must ensure that each returned reference remains valid for as long as its corresponding input reference is valid.

An example for multiple lifetime:

fn print_two<'a, 'b>(x: &'a str, y: &'b str) {

println!("{}, {}", x, y);

}

In the above code, x: &'a str and y: &'b str are independent references. Since the function doesn’t return any of them, Rust doesn’t need to unify their lifetimes — it only requires that each reference stays valid for the duration of the function body.

Imagine,

longest()used in single lifetime like a train pass that must work for both passengers traveling together. The pass expires when the shorter journey ends, so both tickets must be bound to the same validity ('a).But in

print_two(), the passengers just show their tickets separately. Each ticket can have its own expiry ('a and 'b), and that’s fine since nothing depends on both being valid at the same time after the journey.

Let’s understand multiple lifetimes with the example below:

fn longest_pair<'a, 'b>(x: &'a str, y: &'b str) -> (&'a str, &'b str) {

if x.len() > y.len() {

println!("x is longer: {}", x.len());

} else {

println!("y is longer: {}", y.len());

}

(x, y) // ✅ return both references with lifetimes 'a and 'b

}

fn main() {

let string1 = String::from("Rust");

let string2 = String::from("Programming");

let result = longest_pair(&string1, &string2);

println!("Pair: ({}, {})", result.0, result.1);

}

Explanation:

| Code | Explanation |

|---|---|

fn longest_pair<'a, 'b>(x: &'a str, y: &'b str) -> (&'a str, &'b str) |

Defines a function with two lifetimes 'a and 'b. It takes two string references with possibly different lifetimes and returns a tuple containing both. |

if x.len() > y.len() { ... } else { ... } |

Compares the lengths of x and y and prints which one is longer. This part doesn’t affect lifetimes—just logic. |

(x, y) |

Returns both references together. The tuple’s elements carry the lifetimes 'a and 'b, ensuring each reference is only valid as long as its original owner. |

fn main() { ... } |

Starts the program execution. |

let string1 = String::from("Rust"); |

Owns the first string in main. |

let string2 = String::from("Programming"); |

Owns the second string in main. |

let result = longest_pair(&string1, &string2); |

Passes references of string1 and string2 to the function. Compiler checks lifetimes of both. |

println!("Pair: ({}, {})", result.0, result.1); |

Prints both returned references safely, since string1 and string2 are still alive in main. |

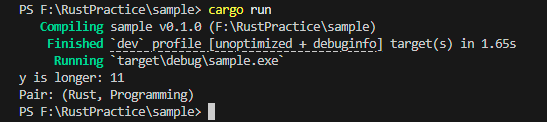

Screenshot: VS code terminal for finding longest using two lifetime references

So far, we’ve dealt with strings. But what happens if we apply multiple lifetimes to something simpler — like integers? Let’s compare both approaches side by side.

| Owned Values (no lifetimes needed) | References with Explicit Lifetimes |

|---|---|

fn sum_owned(a: i32, b: i32) -> i32 { |

fn sum_ref<'a, 'b>(a: &'a i32, b: &'b i32) -> i32 { |

Explanation: Values are copied (since i32 implements Copy), so ownership moves safely. No lifetimes are needed. |

Explanation: We borrow both numbers. Explicit lifetimes 'a and 'b tell Rust how long the references are valid. Return is owned i32, so no lifetime ties it. |

Output: Sum is: 15 |

Output: Sum is: 15 |

Note:

In this example, the return type is an ownedi32. That means the lifetime annotations aren’t about the result itself, but simply ensure that&xand&ystay valid for the duration of the calculation.

📝 Conclusion

In this post, we’ve uncovered the essence of lifetimes in Rust—why they exist, how they work under the hood, and how to explicitly annotate them when the compiler can’t infer. These rules may feel strict at first, but they are the very reason Rust can guarantee memory safety without needing a garbage collector.

In short: single lifetimes tie everything to one timeline, multiple lifetimes allow independent timelines, and together they give the compiler the contracts it needs to keep your program safe.

“We’ve learned how to guide the compiler with explicit lifetimes. But what about the special ‘static lifetime, the hidden rules Rust applies automatically, and how lifetimes truly connect with ownership & borrowing? That’s exactly what we’ll crack in **Part 2**.”

🔜 Next on 🚀Techn0tz!

Cracking Rust Lifetimes – Master Elision, ‘static, and Debugging Errors

Stay Tuned!!