📄 Introduction

When lifetimes clash, Rust steps in like a strict teacher—catching mistakes before unsafe code ever escapes into the wild.

In Lifetimes Part-1, we explored explicit lifetime annotations—Rust’s third memory-safety guardrail. We saw where they apply, why they matter, and practiced with examples. That made lifetimes less mysterious, but it also raised a natural question:

Why don’t we see lifetime annotations everywhere in Rust code?

The compiler fills in the blanks for you—thanks to a feature called lifetime elision rules.

In this post, we’ll:

- Unpack lifetime elision rules (Rust’s built-in “autofill”),

- Explore the special

'staticlifetime, - Connect lifetimes with ownership and borrowing, and

- Learn how to debug common lifetime errors with confidence.

“Think of this post as reading the music sheet behind the melody—the hidden patterns that make your code “just work” without extra noise.”

📜 Lifetime Elision (Elided Lifetimes) – Rust’s Invisible Shortcuts

An elided lifetime is simply a lifetime that the compiler infers for you instead of requiring you to write it explicitly.

In early Rust, you had to write lifetimes everywhere, even for simple functions. To make code less noisy, the Rust team introduced a set of deterministic patterns built directly into the compiler. These patterns let the compiler infer lifetimes automatically in the most common cases—so you don’t have to sprinkle <’a> all over your code.

Here’s the classic example from Part 1:

// with explicit lifetime

fn longest<'a>(x: &'a str, y: &'a str) -> &'a str

// with elision (preferred)

fn longest(x: &str, y: &str) -> &str

Now, how does the compiler know these two signatures mean the same thing?

Because it applies a handful of built-in patterns that tell the borrow checker how to connect input references with output references.

Think of lifetime elision rules like your browser’s autofill feature.

- When you open a form (a function signature), you could manually type your name, email, and address (explicit lifetimes).

- But the browser has smart patterns: if it sees “Name” or “Email,” it automatically fills them in (the compiler’s elision rules).

- This saves you from typing the obvious every time, while still keeping the details correct.

Just like autofill won’t guess in unusual cases (you must type them explicitly), Rust will ask you to write lifetimes yourself when the compiler can’t unambiguously infer them.

To see how these rules are actually applied, we need to talk about two terms that show up in every function signature: input lifetimes and output lifetimes.

- Input lifetimes → lifetimes on function or method parameters.

- Output lifetimes → lifetimes on return values

For example, in the explicit version of longest(), both x and y have input lifetime 'a, and the returned reference uses that same ‘a as its output lifetime:

fn longest<'a>(x: &'a str, y: &'a str) -> &'a str {

if x.len() > y.len() {

x // output lifetime comes from input `'a`

} else {

y

}

}

But when we remove the annotations, how does the compiler know to connect them? The answer is by applying three simple patterns—Rust’s lifetime elision rules.

Let’s walk through each rule and see what it means in practice:

- Rule 1 : Each input reference gets its own distinct lifetime parameter.

fn longest(x: &str, y: &str) // becomes fn longest<'a, 'b>(x: &'a str, y: &'b str) - Rule 2: If there’s exactly one input lifetime, that lifetime is assigned to all output references.

fn longest(x: &str) -> &str // becomes fn longest<'a >(x: &'a str) -> &'a str - Rule 3: If there are multiple input lifetimes, but one of them is

&selfor&mut self, that lifetime is assigned to all output references.

impl Book {

fn get_title(&self, name: &str) -> &str { //becomes fn get_title<'a>(&'a self, name: &str) -> &'a str

if self.author == name {

&self.title

} else {

"Unknown"

}

}

}

With these three rules, the compiler covers almost all common cases automatically. Now, instead of just theory, let’s see them in action with a practical example.

🗂️ Elision Rules in Action

Here is an example that helps you to understand all the elision rules.

// ================= Rule 1 =================

// Each input parameter gets its own lifetime

fn sum(x: &i32, y: &i32) { // compiler sees: fn<'a, 'b>(x: &'a i32, y: &'b i32)

println!("Sum = {}", x + y);

}

// ================= Rule 2 =================

// One input lifetime → output uses the same lifetime

fn square(x: &i32) -> &i32 { // compiler sees: fn<'a>(x: &'a i32) -> &'a i32

x

}

// For rules 1 and 2, plain functions are enough. But for Rule 3, which is specific to methods with &self, we need a struct.

// ================= Rule 3 =================

// Multiple inputs, one is &self → return tied to self’s lifetime

struct Number {

value: i32,

}

impl Number {

// Complex case → needs explicit lifetime

fn compare_and_get<'a>(&'a self, other: &'a i32) -> &'a i32 {

if self.value > *other {

&self.value

} else {

other

}

}

// Simple case → elision works automatically

// Uncomment this version to test:

/*

fn always_return_self(&self) -> &i32 {

&self.value

}

*/

}

fn main() {

let a = 10;

let b = 20;

// Rule 1

sum(&a, &b); // 30

// Rule 2

let sq = square(&a);

println!("Square = {}", sq * sq); // 100

// Rule 3-Complex case

let num = Number { value: 15 };

let bigger = num.compare_and_get(&b);

println!("Bigger = {}", bigger); // 20

// Rule 3-Simple case

// Uncomment the method above, then run this:

/*

let num = Number { value: 15 };

let only_self = num.always_return_self();

println!("Always return self = {}", only_self); // 15

*/

}

Note: If a method always returns

&self.value, elision alone works. But since our example may also return another reference, we must explicitly tie them together with'a.

💡 Try it yourself:

Uncomment always_return_self and the corresponding call in main(). Notice that here you don’t need <’a> — because the return value clearly comes from &self only.

Most of the time, these invisible shortcuts save you from writing <’a> everywhere. Only when multiple lifetimes compete you need to step in with explicit annotations.

So far, every reference lifetime has been borrowed from some input.

But what if a value doesn’t borrow at all—and instead lives for the entire duration of the program? That’s where Rust’s special 'static lifetime comes in.

♾️ ‘static: The Clock Tower of Rust Lifetimes

The 'static lifetime is the longest lifetime in Rust. It means a value is guaranteed to live for the entire duration of the program.

Think of a city clock tower: people (variables) come and go, but the tower (a ‘static resource) stays there, ticking as long as the city exists.

In Rust, 'static values show up in three common places:

- String literals (automatic ‘static)

- Global Data (static and const)

- Trait bounds with

'static

Let’s explore each with examples.

- String Literals (automatic ‘static)

String literals are stored directly in your program’s binary. That’s why they automatically have a'staticlifetime.

fn quote() -> &'static str {

"Knowledge is power."

}

fn main() {

let q = quote();

println!("{}", q);

}

- Global Data (static and const)

Anything declared withstatic or constalso has a'staticlifetime. These values are stored in memory regions that exist for the whole program.

static GREETING: &str = "Welcome!";

fn main() {

println!("{}", GREETING);

}

- Trait bounds with ‘static

In generics,'staticis often used as a bound. This usually means:- the type owns its data or

- it doesn’t borrow from any shorter-lived source.

fn takes_static<T: 'static>(val: T) {

// val is guaranteed not to borrow temporary data

}

⚠️ A Note of Caution

Just because ‘static lasts for the whole program doesn’t mean you should sprinkle it everywhere. Overusing it can over-constrain your code, making it less flexible. Reserve it for truly long-lived values like literals, constants, and globals.

We’ve seen how Rust can save us from lifetimes entirely (elision), and how some values can even live forever ('static). Now it’s time to see how lifetimes fit alongside Rust’s other memory safety pillars.

🔖 Ownership vs Borrowing vs Lifetimes

If you want a quick refresher, check out Ownership post and Borrowing post to revisit the core concepts.

| Feature | Ownership | Borrowing | Lifetimes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Who controls the value? | The owner variable | The owner still controls it; borrower has temporary access | Compiler tracks how long references to the value are valid |

| How long can you use it? | Until it goes out of scope | Until the borrow ends (function return, block end, etc.) | As long as the declared/reference lifetime allows |

| Does control move? | ✅ Yes | ❌ No – access is temporary | ❌ No – lifetimes don’t move data, they only enforce validity |

| Can you modify it? | ✅ Yes, if it’s mutable | ✅ Yes, only with a mutable borrow (&mut) |

❌ N/A – lifetimes don’t decide mutability, just ensure safe reference usage |

| Number of simultaneous accesses | One owner at a time | Many immutable borrows or one mutable borrow | Many references possible, but lifetimes ensure they never outlive the data |

| When is memory freed? | When the owner goes out of scope | When the owner goes out of scope (borrowers don’t free memory) | Same as ownership – lifetimes just ensure references don’t exist past cleanup |

| Main Purpose | Manage who owns and frees the memory | Allow safe temporary access without moving ownership | Prevent dangling references by tying references to the lifetime of the data |

| Example | Moving a string into another variable | Passing a reference to a function without cloning | Function with multiple references annotated with lifetimes to enforce validity |

🛠️ Debugging Lifetime Errors in Rust

Even though lifetimes make sense in theory, Rust often throws confusing errors when we forget, mismatch, or misuse them. Let’s look at some common errors — why they happen, and how to fix them with correct code.

Error 1 – Missing Lifetime (Elision Rule Violation)

fn longest(x: &str, y: &str) -> &str {

if x.len() > y.len() {

x

} else {

y

}

}

fn main() {

let s1 = String::from("Rust");

let result;

{

let s2 = String::from("Ownership");

result = longest(s1.as_str(), s2.as_str());

println!("Longest: {}", result);

}

}

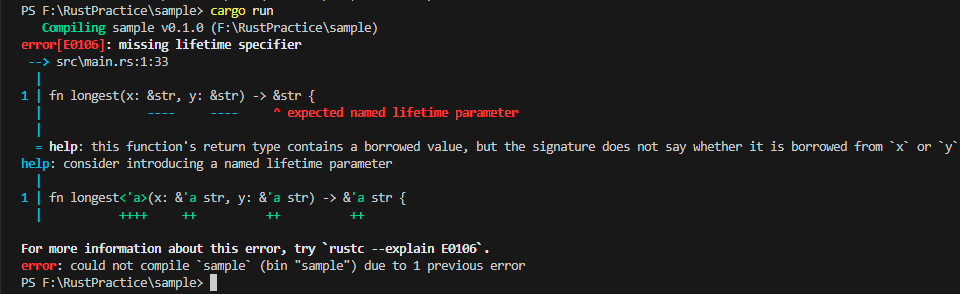

Error Message Screenshot:

Why it happens:

The compiler can’t infer how long the returned reference should live, because both inputs go out of scope independently. Without an explicit lifetime, Rust doesn’t know if the returned reference will be valid.

How to Fix:

Add a lifetime parameter that ties the returned reference to the lifetime of the inputs.

fn longest<'a>(x: &'a str, y: &'a str) -> &'a str {

if x.len() > y.len() {

x

} else {

y

}

}

fn main() {

let s1 = String::from("hello");

let s2 = String::from("world!");

let result = longest(&s1, &s2);

println!("Longest is: {}", result);

}

💡 Try it yourself:

Remove the exclamation mark from "world!". Does it print hello or world? Why?

Error 2 – Explicit Lifetime Mismatch

fn mismatch<'a, 'b>(x: &'a str, y: &'b str) -> &'a str {

y // ❌ returning 'b reference as 'a

}

fn main() {

let s1 = String::from("apple");

let s2 = String::from("banana");

let result = mismatch(&s1, &s2);

println!("Mismatch result: {}", result);

}

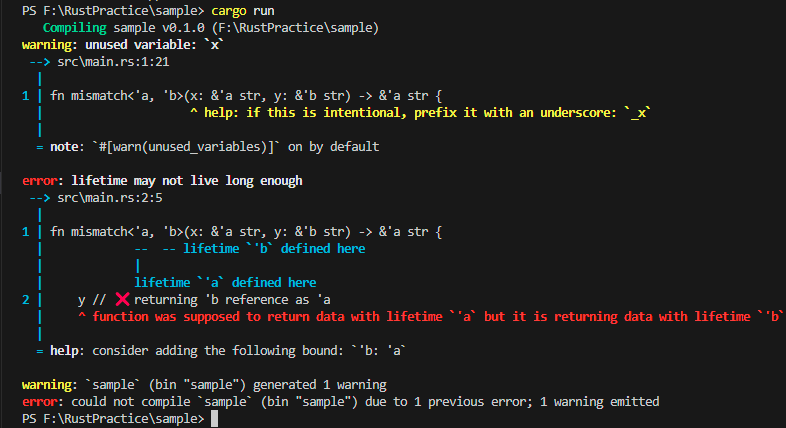

Error Message Screenshot:

Why it happens:

Even with explicit lifetimes, the compiler checks that the returned reference actually lives as long as the declared lifetime. Returning a reference with a different lifetime than promised violates the contract.

How to Fix:

Use the same lifetime parameter for all references involved in the return type, ensuring the compiler can guarantee safety.

fn mismatch<'a>(x: &'a str, y: &'a str) -> &'a str {

if x.len() > y.len() {

x

} else {

y

}

}

fn main() {

let s1 = String::from("apple");

let s2 = String::from("banana");

let result = mismatch(&s1, &s2);

println!("Mismatch fixed result: {}", result);

}

💡 Try it yourself:

In the fixed code, try changing y and let s2 to &'static str and see if the code complies

Error 3 – ‘static Lifetime Misuse

fn wrong_static() -> &'static str {

let local = String::from("temporary");

&local // ❌ returns reference to local var as 'static

}

fn main() {

let result = wrong_static();

println!("Result: {}", result);

}

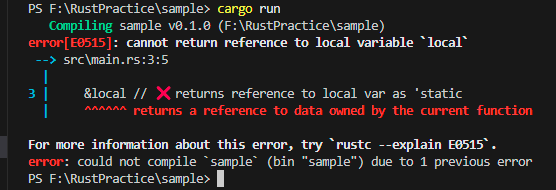

Error Message Screenshot:

Why it happens:

Declaring a ‘static lifetime doesn’t extend the life of local variables. Returning a reference to a local variable as ‘static is invalid because the variable is dropped at the end of the function.

How to Fix:

Return an owned value (String) instead of a reference or return a reference to a value that truly lives for the entire program, such as a string literal or a global static variable.

1️⃣ Return owned value instead

fn correct_static() -> String {

let local = String::from("temporary");

local

}

fn main() {

let result = correct_static();

println!("Result: {}", result);

}

2️⃣ Use a String literal

fn correct_static_literal() -> &'static str {

"I live forever"

}

fn main() {

let result = correct_static_literal();

println!("Result: {}", result);

}

💡 Try it yourself:

- Create a global: static WELCOME: &str = "Hello from global!"; and return it with `'static` → ✅ works fine.

- Now replace it with static WELCOME: String = String::from("hello"); → ❌ compiler rejects (heap data not allowed in static).

🎯 Conclusion

In Part 2, we expanded on what we learned in Part 1 by exploring lifetime elision, ‘static lifetimes, and common lifetime errors. You now understand how Rust infers lifetimes automatically, how to annotate them explicitly when needed, and how ‘static values live for the entire duration of the program.

Lifetimes are Rust’s compile-time guarantee that references never outlive the data they point to, helping you avoid dangling references without any runtime cost.

With these concepts in your toolkit, you can confidently interpret compiler messages, fix lifetime errors, and write safe, efficient Rust code.

🔜 Next on 🚀Techn0tz!

We’ll put Rust’s GUI design, state management, and CSV-based storage into action with a hands-on Teacher Assistant App — watch these concepts come alive in real Rust code.

Stay Tuned!!