📄 Introduction

💬 “Why can’t I use this variable again?”

💬 “Why does Rust keep yelling about ‘move’ or ‘borrow’?”

If you’ve ever run into these mysterious compiler messages, you’ve just touched the very soul of Rust — its memory safety model.

Unlike in many other languages where memory bugs lurk in the shadows and crash your program at runtime, Rust catches them at compile time. That’s part of what makes it powerful, safe, and… at times, a bit confusing for newcomers.

If that sounds familiar, you’re not alone — and you’re exactly where you need to be.

🔍 Welcome to the next part of our Rust Basics!

In this next part of Rust Basics, you’ll get a bird’s eye view of the three invisible forces that control how memory works in Rust:

- Ownership

- Borrowing

- Lifetimes

These aren’t just rules — they’re the core logic behind how Rust achieves memory safety without a garbage collector. Once you understand these, the rest of Rust will start to make a lot more sense.

Still confused? Don’t worry — each topic is broken down step-by-step, with clear explanations, visuals, and hands-on examples. Take your time exploring each — because in Rust, memory safety is built one clear concept at a time. 🧠🛠️

✅ Ready to unravel Rust’s most powerful mystery? Let’s begin with Ownership — the first thread that holds it all together.

🏷️ Ownership in Rust – The Golden Rule

In this post, you’ll explore how Rust assigns ownership, learn the three golden rules, and see why moves and clones matter — all explained with practical examples and visuals.

🧠 What is Ownership?

In Rust, ownership is the foundation of how memory is managed — with no garbage collector running in the background.

Instead of freeing memory manually or waiting for a GC, Rust uses the concept of ownership to automatically deallocate memory when it’s no longer needed. This happens at compile time, and it’s all made possible through three simple but powerful rules.

🔍 Before we dive into the rules of ownership, let’s briefly see how Rust stores data:

- Stack – Fast and efficient. Stores fixed-size, known-at-compile-time data like integers and booleans.

- Heap – Flexible but slower. Stores growable or dynamically-sized types like String, Vec, and user-defined structs.

➡️ Rust enforces rules so that:

- Stack data is copied safely,

- Heap data is either moved or cloned to avoid memory bugs.

📜 The 3 Golden Rules of Ownership

Rust enforces three core rules to manage ownership and memory safely:

-

Each value in Rust has a variable that’s its owner

→ The owner is responsible for the value’s memory. -

There can only be one owner at a time

→ This prevents accidental data races or double frees. -

When the owner goes out of scope, the value is dropped

→ Rust automatically frees the memory — nofree()or garbage collector needed!

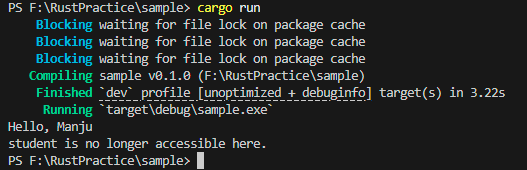

fn main() {

{

let student = String::from("Manju");

println!("Hello, {}", student);

} // student variable is dropped here, and memory is freed

println!("student is no longer accessible here.");

}

🧹 No need to write free(student) — Rust handles it for you.

Screenshot : Output of the above code in the VS Code terminal

🔍 Ownership in Action

Let’s see how ownership works in Rust with a small example.

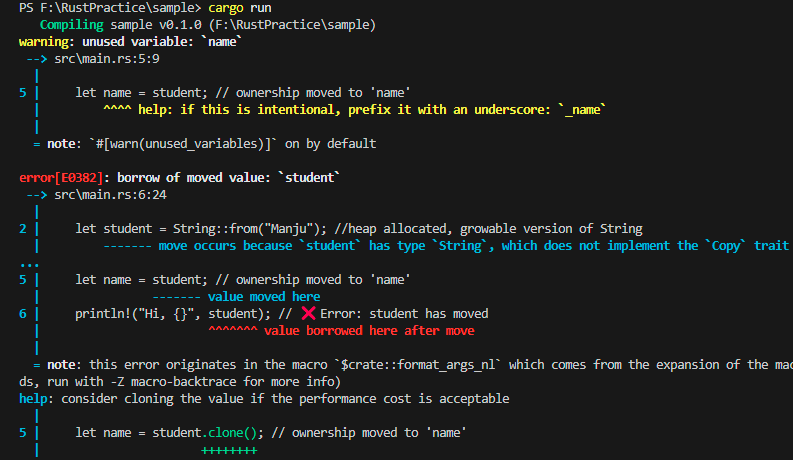

fn main() {

let student = String::from("Manju"); //heap allocated, growable String

println!("Hello, {}", student);

let name = student; // ownership moved to 'name'

println!("Hi, {}", student); // ❌ Error: student has moved

}

Screenshot : Compile-time error in VS Code terminal

Explanation:

| Line | Description |

|---|---|

let student = String::from... |

student variable owns the String “Manju”. |

println!("Hello, {}", student) |

prints a greeting using the student value |

let name = student |

ownership transferred to name. |

println!("Hi, {}", student) |

causes a compile-time error — student was moved |

Note :

🧠 Ownership determines who “owns” a value in memory and is responsible for cleaning it up.

🔁 When you assign or pass values, Rust may move, copy, or let you clone them explicitly — depending on the data type

💼 Ownership Techniques in Rust

To manage memory safely, Rust uses three core strategies: Move, Copy, and Clone. Let’s break each down.

📦 Move in Rust – Who Owns the Box Now?

A move happens when a non-Copy value (like a String or Vec) is assigned to another variable. The ownership is transferred, and the original variable becomes invalid.

Let’s see how it works with an example

fn main() {

let name = String::from("Rustacean");

let new_name = name; // ownership is moved from name to new_name

println!("{}", name); // ❌ Error: value was moved

}

Explanation:

- The heap-allocated string “Rustacean” is initially owned by the variable

name. - When we write

let new_name = name;, the ownership of the string is moved tonew_name. From this point,nameis no longer valid. - If you try to access

nameafter the move (e.g., withprintln!("{}", name);), the compiler throws an error. - Why? Because if both

nameandnew_namewere allowed to own the same heap memory, Rust wouldn’t know which one should clean it up — leading to a double free bug (a serious memory safety issue). - To prevent this, Rust invalidates

nameafter the move. Onlynew_nameremains the valid owner, ensuring safe memory management at compile time.

🧬 Copy – When Values Are Duplicated, Not Moved

Not all values in Rust are moved when assigned to a new variable. Some are copied, meaning both the original and the new variable can be used independently.

Rust performs a copy only for types that implement the Copy trait — usually simple, fixed-size values like integers, booleans, and characters.

Let’s understand it with a small example.

fn main() {

let age = 25; // i32 is a Copy type

let new_age = age; // value is copied, not moved

println!("age: {}", age); // ✅ Works fine

println!("new_age: {}", new_age); // ✅ Works fine

}

Explanation:

- The integer

25is stored on the stack, andi32implements theCopytrait. - So when we assign

agetonew_age, Rust copies the value — both variables hold the same data independently. - Unlike String, no ownership transfer happens here, and both age and new_age remain valid throughout their scope.

- This is possible because primitive types like integers, floats, and booleans are lightweight and safe to duplicate.

🧪 Clone – When You Need a Real Deep Copy

Unlike simple types that are automatically copied, complex heap-allocated data like String, Vec, or HashMap do not implement the Copy trait. Instead, if you want to create a true, independent duplicate of such values, you need to explicitly clone them.

Let’s understand it with a small example.

fn main() {

let city = String::from("Bangalore");

let second_city = city.clone(); // deep copy

println!("City 1: {}, City 2: {}", city, second_city); // ✅ Works!

}

Explanation:

cityis a String (stored on the heap).let second_city = city.clone(); makes a complete copy of the string’s data in a new memory location.- Both city and second_city now own separate copies of the data, so they’re both valid.

- This avoids ownership issues without invalidating the original variable.

🔁 Note : Cloning can be more expensive than copying, especially for large data structures — because it duplicates data from the heap.

So, use .clone() only when truly needed — Rust makes you write it explicitly to avoid hidden performance costs.

🔖 Ownership Summary: Move vs Copy vs Clone

| Concept | Memory Involved | Affects Which Data Types? | What Happens? | Can Use Original After Operation? | Example |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 🟡 Move | Heap (mostly), sometimes stack | Heap-allocated types like String, Vec, Box, etc. |

Ownership is transferred to a new variable. Old variable becomes invalid. | ❌ No | let b = a; (for String) |

| 🟢 Copy | Stack | Simple, fixed-size types: i32, char, bool, floats, tuples of Copy types |

Value is duplicated. No ownership transfer. | ✅ Yes | let y = x; (for i32) |

| 🔵 Clone | Heap (usually) | Heap types that implement Clone trait: String, Vec, etc. |

Performs a deep copy of the value on the heap. You manually call .clone(). |

✅ Yes | let b = a.clone(); |

📝 Try it Yourself! - Example

Here is a simple example that helps you to understand move, copy and clone

fn main() {

// Move

let book = String::from("Rust Book");

let shelf = book; // Ownership moved

println!("Book: {}", shelf);

//println!("Book: {}", book);// ❌ Uncomment to see the move error

// Copy

let a = 5;

let b = a; // Copy because integers implement the Copy trait

println!("a = {}, b = {}", a, b); // ✅ Still valid

// Clone

let notebook = String::from("Notes");

let copy_notebook = notebook.clone(); // Explicitly clones the heap data

println!("Original: {}, Clone: {}", notebook, copy_notebook); // ✅ Both work

}

In the above code, uncomment the line `println!(“Book: {}”, book); and see what happens!!

🎯 Conclusion

Ownership in Rust isn’t just a rule — it’s the foundation that ensures memory safety with zero runtime overhead. Once you grasp this invisible thread of control, the language starts making powerful sense. From here, the next step is understanding how Rust lets you share without giving up ownership — through borrowing.

🌱 Ready to Grow Further?

So far, we saw how ownership transfers or duplicates data. But what if you just want to borrow it temporarily, like a library book?

That’s where Rust’s borrowing model and lifetimes shine.

🔄 What’s Next on Techn0tz?

In the next post, we’ll explore:

Borrowing in Rust – The Art of Lending Data